Chicanery, 1960 Part III

“Landslide Lyndon” and the “Lone Star State”

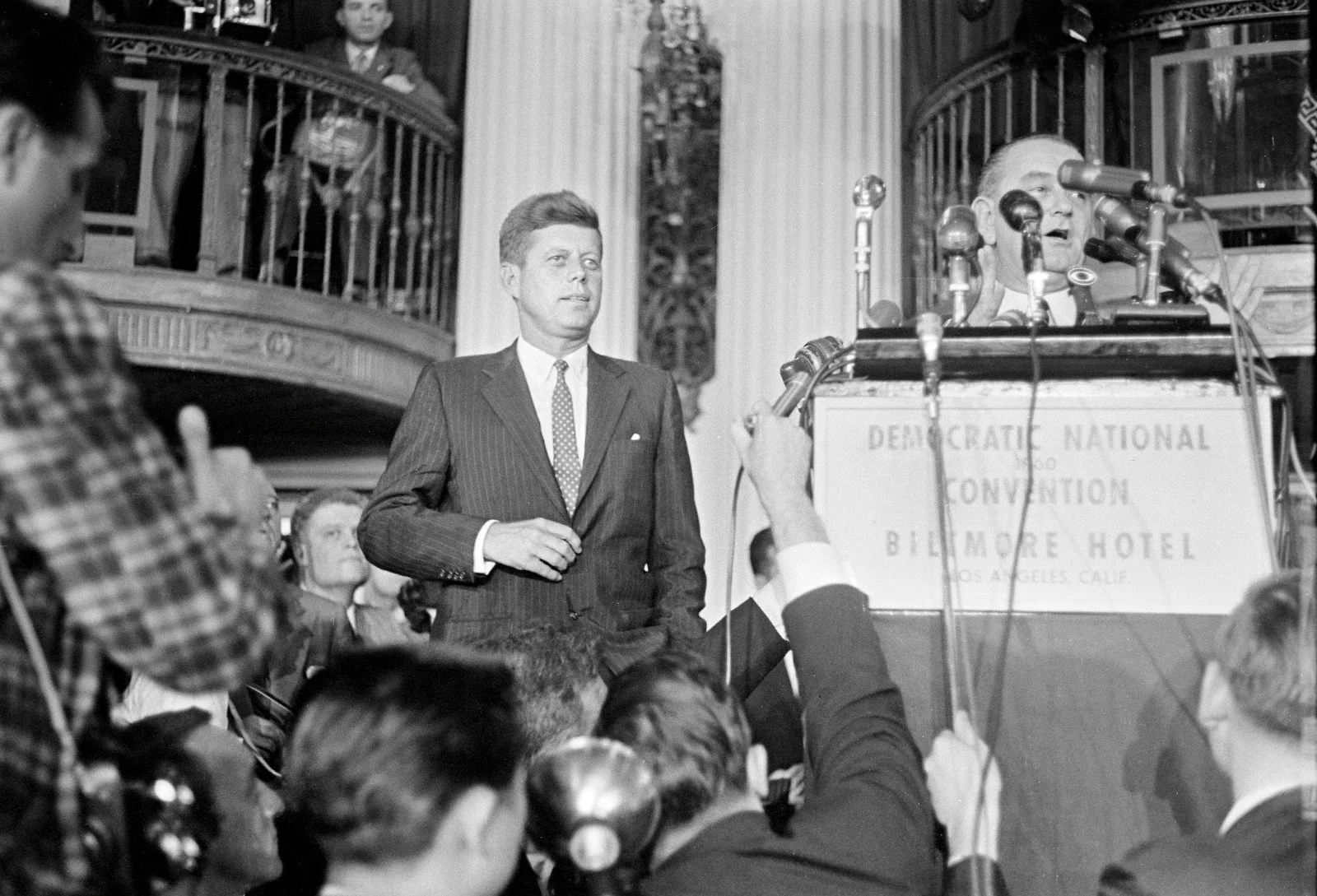

Senator John Kennedy at the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, 1960

Confident as ever, Jack Kennedy landed in Los Angeles mid- July 1960 for Democratic National Convention. During the primaries, he’d faced concerns related to his Catholic religion, age and experience but still managed to charm voters and gain a lot of momentum. He had plenty of challengers. Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota dropped out after Kennedy beat him in the West Virginia Primary. Adlai Stevenson, former governor of Illinois, had been the Democratic nominee in the last two elections, and although he refused to campaign again, he also refused to rule out another run if he was drafted to do so. Kennedy visited him at his home in Libertyville, IL early on to offer him the position of “Secretary of State” in exchange for an endorsement, but was turned down. At the convention, Eleanor Roosevelt, actor Henry Fonda and former head of MGM, Dore Schary, laboriously promoted the former governor, prompting Robert F. Kennedy, who was working on his brother’s campaign, to threaten Stevenson in his hotel room, demanding he throw his weight behind Jack. Stevenson in return, ordered the younger Kennedy to leave immediately.

In total, including the three mentioned above, eleven candidates would receive at least one vote before Kennedy was certified as the winner with 52.89%. His closet competitor, Lyndon Baines Johnson, had secured 26.84% without spending a moment on the campaign trail. Johnson, at the time, was the majority leader of the U.S. Senate. Historians often cite him as the most effective majority leader there ever was, and specifically applaud his ability to gather intel, which he would subsequently use to manipulate and control his colleagues. One of his advisors recalled later how Johnson would send senators on NATO trips to keep them from casting dissenting votes, if it was in his interest to do so. Then, of course there was “the treatment”, a verbal beatdown that he would doll out in the Senate cloakroom and occasionally in full view on the Senate floor. Senators on the receiving end of this were typically unable to interject- Johnson always seemed to anticipate what they might want to say- and they would be left stunned or unsure of how to proceed.

Although he was urged to seek the presidency starting in 1959, Johnson was reluctant to leave Washington D.C. He hoped to rely on his record, his support base in the south and his allies in the Democratic party. He underestimated Kennedy, believing he was too young and too naive to capture the nomination. At the convention, when he became aware of the writing on the wall, he quickly formed a “Stop Kennedy” coalition alongside Gov. Stevenson and Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri. He also let the press in on a little secret about JFK that he and his family desperately wanted to keep quiet: Kennedy had Addison’s disease, among a plethora of other ailments, and depended on cortisone treatments to stay alive. This was a dirty tactic perhaps, but it was absolutely true. All around the country, the Kennedy’s had arranged to have cortisone and DOCA available in safety deposit boxes, for emergencies. As a child, he’d nearly died of scarlet fever. He had IBS, spastic colitis, frequently suffered from urinary tract infections, prostatitis and a duodenal ulcer. His lower back pain was so severe, he was initially rejected from the U.S. Army and Navy when he enlisted during WWII.

Robert Kennedy, just as savvy a political player as Johnson was, combated the leak first by denying it, and then he found two doctors willing to publish a report describing his brother’s health as “excellent”.

Johnson meets with the Kennedy brothers at the Democratic National Convention, 1960

Johnson may have lost the Democratic party’s blessing, but he proved that his reputation preceded him. Not that it was necessary. The Kennedy’s, smart enough to learn from the old adage “keep your friends close and your enemies closer”, sought to use Johnson’s resources to win not just in November, but to push their agenda forward over the next four to eight years. So, like their father had advised them to do, Jack and Bobby extended their offer to Johnson- which he accepted, and was then officially named as JFK’s running mate.

* * * * *

Kennedy had won Texas by 46,257 votes. This meant it would take a lot more effort to find enough evidence of fraud to flip the state for Richard Nixon than it would in Chicago. Republicans declared shortly after the election that tens of thousands of votes were fraudulent and tens of thousands of other votes had been fraudulently invalidated. There was contention surrounding the fact that many counties used paper ballots that required voters to sign a numbered poll list, making it obvious who they intended to vote for. There was also the matter of a new law, requiring voters to not just indicate who they wanted to vote for on their ballots but also scratch out the names of all those they didn’t want to vote for as well. A clause existed- if the voter’s selection was obvious- it would be counted regardless of their adherence to the law. Republicans alleged that this had been abused, and votes for Vice President Nixon had been invalidated while votes for Kennedy were always counted.

Along the Mexican border, the Rio Grande Valley was known as a place where votes could be bought. In close races, the tally from those counties typically came in late with just enough votes to a given candidate over the top. Rumor has it that the numbers on the poll tax receipts for each household were retrieved and the people living there were told not to vote. Based on those household counts, votes were then given to Kennedy. There were also allegations of slow counting, in which Texan political bosses would wait to see what margins needed to be covered before resuming their count, which was then presumably manipulated in the Democrat’s favor.

Back in 1948, Coke Stevenson, a Democrat who was born in a log cabin and was elected Governor of the “Lone Star State” in 1941, challenged then U.S. Representative Lyndon Johnson for an open senate seat. Johnson flew a helicopter from town to town and sent out false and negative mailing- flush with money from his backer, the Brown and Root Company (now Halliburton). On election night, Coke Stevenson- who’d been massively outspent- was still projected to win. He was popular, respected, and totally disinterested in playing Johnson’s game. Later that night, a mysterious ballot box arrived from Jim Wells County in southern Texas with 202 votes inside, putting Johnson in the lead by 87 votes. A recount handled by the Democratic State Central Committee revealed that all the names in the box were in alphabetical order, written with the same pen and in the same handwriting. According to local legend, Johnson and his men were going through cemeteries in the days following the election, taking the names of dead Mexicans from tombstones to register as voters. They couldn’t decipher one of the names and asked Johnson what they should do about it. “Give him a name.” Johnson apparently said. “He’s got just as much a right to vote as the rest of them in this cemetery do.” Johnson’s nickname “Landslide Lyndon” is often mistakenly believed to have come from his 1964 victory against Sen. Barry Goldwater. In actuality, it was coined in 1948 as a cheeky reference to this elections questionable outcome.

In the thirteen precinct of Jim Wells County, known since then as “Box 13”, Kennedy had won with 1,144 votes to Nixon’s 45. No serious investigations were ever conducted in Texas however. The three men who headed the canvassing board were all Johnson’s allies: Governor Price Daniel, State Attorney General Will Wilson and Texas Secretary of State Zollie Steakly. A Republican petition to challenge the results in 1960 was blocked- the stated reason being there was no reason to believe vote tampering had occurred.

Works Cited

Allswang, J.M. (2019) Bosses, machines, and urban voters. Baltimore, MD, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, Project Muse.

Binder, J.J. (2020) ‘DID THE CHICAGO OUTFIT ELECT JOHN F. KENNEDY PRESIDENT?’, themobmuseum.org, 22 October. Available at: https://themobmuseum.org/blog/did-the-chicago-outfit-elect-john-f-kennedy-president/.

Bomboy, S. (2017) ‘The drama behind President Kennedy’s 1960 election win’, constitutioncenter.org, 7 November. Available at: https://constitutioncenter.org/amp/blog/the-drama-behind-president-kennedys-1960-election-win (Accessed: 01 October 2024).

Carlson, P. (2000) ‘Another Race To the Finish’, The Washington Post, 17 November.

Cheney, K. (2022) ‘See the 1960 Electoral College certificates that the false Trump electors say justify their gambit’, POLITICO, 7 February.

Royko, M. (1988) Boss: Richard J. Daley of Chicago. New York: Plume.

Shesol, J. (2022) ‘Did John F. Kennedy and the Democrats Steal the 1960 Election?’, New York Times, 18 January.